The four-eyed witness to Africa's vanishing grasslands

Plus, science finally learns how seals can hold their breath for so long!

By Dan Fletcher

Here is today’s audio edition:

Good morning — while I’m off the road and recovering at home for a little bit, I wanted to start a series introducing you to some of the lesser-known threatened and endangered species around the world.

It’s part of the nature of online funding that a few species end up getting outsized attention and dollars, while others languish with few resources at all. We saw this last month with the pygmy hippo, where even the massive viral phenomenon of Moo Deng didn’t translate into conservation dollars for her wild brethren. (Our paying subscribers helped to change that with last month’s FUZZ Funds donation to Flora and Fauna.)

But there’s obviously more to do. So today’s newsletter takes us to the Kenyan-Somali border, a harsh part of the world where an ancient antelope is just barely holding on through some unique community conservation efforts.

Want to help support endangered species around the world? Join FUZZ as a paid subscriber, and 100% of your monthly or annual support will go directly to conservation causes we vote on each month. You can upgrade your subscription at the button below and join 36 other FUZZ community members making a difference each month.

The last antelope standing in an ancient lineage

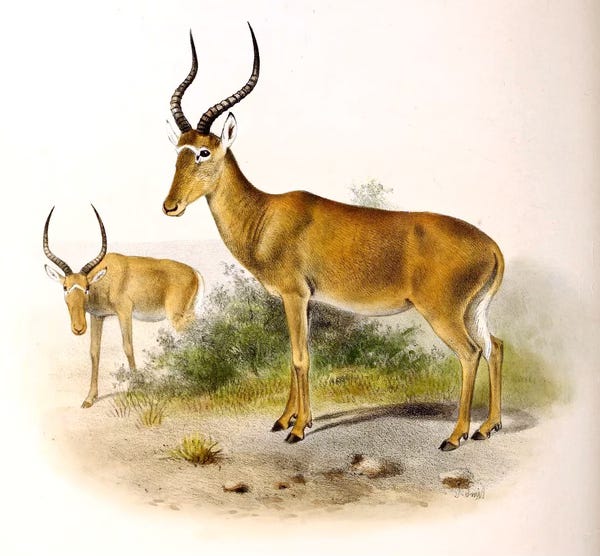

Meet the hirola antelope, also known as the "four-eyed antelope," with distinctive dark facial glands that create the illusion of a second set of eyes watching you from the grasslands. But who's watching out for them? With fewer than 500 hirola remaining in the wild, they've earned the grim distinction of being the world's most endangered antelope species, yet they rarely appear in conservation headlines or social media campaigns.

And their plight is uniquely urgent, as these elegant, medium-sized antelopes with their distinctive lyre-shaped horns are the last surviving members of their entire genus. While their distant relatives in the same family — hartebeests, wildebeests, and topis — still roam African savannas in viable numbers, the hirola carries the evolutionary legacy of their entire branch alone.

These antelope are seriously unique:

Their pre-orbital glands (which create the "four-eyed" appearance) are among the largest of any antelope species and can be opened wide when the animal is excited or alarmed

Hirola can go their entire lives without drinking water, getting all their moisture from the plants they eat

They have a remarkable memory for locations, returning to the same grazing areas season after season even when vegetation appears more abundant elsewhere

Like the manul, they’re considered a "living fossil" and have remained virtually unchanged for over 3 million years

Despite their declining numbers, hirola maintain moderate genetic diversity, suggesting they've survived previous population bottlenecks

Even in recent times, the hirola used to be much more numerous. Scientists classify them as a "refugee species" — once widespread across East Africa, they've been pushed into increasingly marginal territory along the Kenya-Somalia border where survival becomes more difficult with each passing year. Think of it as an ecological emergency shelter, a place for the hirola to hold to on while their true home vanishes around them.

What makes their decline so darkly fascinating is how it reveals the invisible threads that connect ecosystems. First, there was a deadly outbreak of rinderpest in the 1970s, which decimated population numbers. Then, after poachers eliminated approximately 5,000 elephants from the region during the 1970s, there was a cascade of environmental changes. Without elephants pushing over trees and creating clearings, woody vegetation crept across the landscape unchecked. Then tree cover increased by 251% between 1985 and 2012, transforming what was once open grassland into dense woodland.

Dr. Abdullahi Ali grew up herding cattle alongside hirola in eastern Kenya. "Seeing the hirola grazing peacefully with our livestock created in me a very strong personal passion and attachment to this species," he told the Society for Ecological Restoration. As he watched their numbers dwindle, he founded the Hirola Conservation Program to develop local solutions for their protection.

"There was a time the survival of the hirola was considered a fairy tale," says Dr. Ali. "And although part of this perception is still rife, we can now see light at the end of the tunnel."

That glimmer of hope comes from trying to address both immediate threats and long-term habitat needs. A predator-proof sanctuary supported by the Northern Rangelands Trust at Ishaqbini Conservancy protects hirola from lions while researchers and community members work to restore the surrounding habitat — manually clearing invasive trees and replanting native grasses across thousands of acres to essentially recreate the ecosystem functions that elephants once provided.

Here’s Dr. Ali explaining the grassland restoration project:

Inside this protected area, calving rates have increased substantially. And despite their small population, genetic studies show that hirola have enough genetic diversity to recover if their habitat can be restored.

The hirola's future hangs in the balance, but their story reminds us that conservation isn't just about saving individual species. It's about understanding and preserving the complex relationships that bind ecosystems together — from elephants to antelopes to the grasses beneath their feet. Sometimes the most endangered species aren't the charismatic megafauna that capture our attention, but the quiet guardians of forgotten grasslands, watching the world change through four melancholy eyes.

Lead photo from the Northern Rangelands Trust.

Quick links!

A gray wolf brought to Colorado from Canada as part of the state's reintroduction efforts was killed by Wildlife Services in Wyoming after being found near the site of five sheep kills. The wolf had traveled from Colorado into north-central Wyoming, where officials confirmed "evidence consistent with wolf predation" before removing the animal. Meanwhile in Oregon, authorities are offering a $30,500 reward for information about the illegal killing of a breeding male wolf from the Metolius pack, highlighting the ongoing challenges these animals face as they navigate landscapes shared with humans and livestock.

Ever wonder how seals avoid drowning during their lengthy underwater dives? Dr. Chris McKnight did, and found that seals possess a unique ability to cognitively sense oxygen levels in their blood, allowing them to know precisely when they must return to the surface. This adaptation helps explain how marine mammals can spend most of their lives underwater without access to air. The research involved studying six juvenile seals diving for fish while researchers adjusted oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the air. "To find such a fundamental aspect of the evolution of marine mammals that is so central to a huge part of what they do — dive — is incredibly exciting," Dr. McKnight said.

Fascinating read, thanks Dan! I had no idea elephants played such a big role in engineering their environments, and that it would have such a big impact on other species too. Glad to hear there's still hope for the hirola.