Stolen wildlife can't speak, but their bones can

Plus the world's rarest horse turns up in a kill pen in Kansas. (Don't worry, he was saved.)

By Dan Fletcher

When I think of wildlife crime, I picture rangers tracking poachers through dense forests or investigators infiltrating black markets. But sometimes, fighting wildlife crime requires a completely different kind of detective work — the microscopic kind that happens in laboratories, using elements so obscure they rarely make it into everyday conversation.

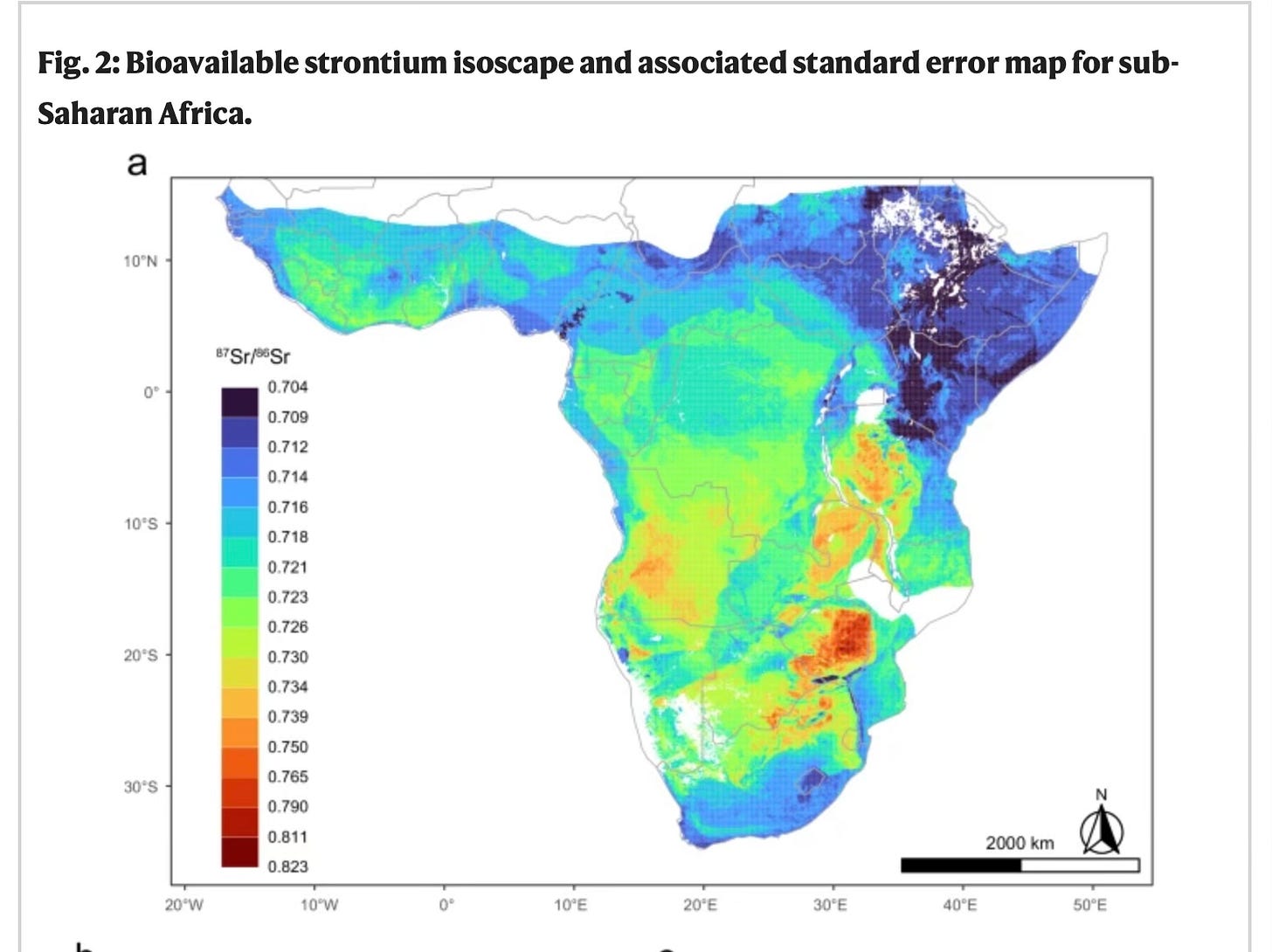

A study published this year in Nature Communications has created the most comprehensive "strontium map" of Africa ever developed. This scientific breakthrough isn't just changing how we understand human history — it's providing an unexpected new tool in the fight against wildlife trafficking.

Strontium is a naturally occurring element found in rocks, soil, water, and living organisms. It exists in several forms called isotopes, and the ratio of these isotopes varies across different geographic regions based on the underlying geology. Think of it as a geological fingerprint unique to each location.

When animals (including humans) consume local food and water, they incorporate these specific strontium signatures into their bones and teeth. This creates a permanent record of where they lived — a chemical passport that can't be forged.

The research team, which included over 100 scientists working across 24 African countries, collected more than 2,000 samples, including plants, soils, and small animal remains, to build their comprehensive map. This collaborative effort took over a decade to complete and required international coordination among experts from diverse fields, including archaeology, botany, zoology, and ecology.

The strontium map was initially developed to help trace the origins of victims of the transatlantic slave trade. By analyzing tooth enamel from remains found in slave cemeteries in Charleston, USA, and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, researchers could identify the specific regions in Africa where these individuals were born — giving descendants crucial information about their ancestral origins that slavery had previously erased.

But the same technology also offers a powerful new tool for wildlife conservation. Dr. Nikki Tagg, the Head of Conservation from the Born Free Foundation, was among the conservationists involved in the data collection and realized the implications. When authorities confiscate animal parts from illegal traffickers — whether elephant ivory, pangolin scales, or even live animals like baby chimpanzees — they can now analyze their strontium signatures and determine exactly where these animals were taken from.

This precise geographic information helps identify wildlife trafficking hotspots, allowing conservation organizations to target their protection efforts more effectively and potentially disrupt trafficking networks at their source. Africa is vast, and conservation resources are constrained, so being able to more accurately pinpoint interventions to stop wildlife trafficking at its source is potentially a huge boon.

Quick links! 🔗

Speaking of wildlife trafficking: once extinct in the wild, the world’s rarest horse — the Przewalski’s (pronounced sheh-VAL-ski) — somehow ended up misidentified and nearly sold for slaughter in a Kansas kill pen. Enter Shrek, a shaggy, mohawked gelding whose odd looks caught the eye of a Colorado family. Genetic testing confirmed the impossible: Shrek is a purebred Przewalski’s, a living relic of Mongolia’s grasslands. While he won’t be passing on his genes, Shrek now grazes peacefully with his new herd happily living out his days on a rescue ranch in Aurora. Not bad for a “mule” rescued on Facebook.

Above the rush of LA’s 101 freeway, the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing is taking shape — the largest of its kind in the world. Designed to reconnect the fragmented Santa Monica Mountains, this bridge will give mountain lions, bobcats, frogs, and even butterflies a safe path across one of the busiest roads in the U.S. Built with native soil and over 5,000 local plants, it’s more than a structure — it’s a lifeline for wildlife and a big step toward undoing decades of habitat loss caused by highways. Construction is expected to be finished by the end of 2026.

What an interesting read, thanks Dan! So cool to hear about this new tool for combating wildlife trafficking, I never would've guessed something like that would be possible!