By Dan Fletcher

Here’s the audio edition for today!

I have to admit — I was in need of some good news to end this week and maybe you need some, too. So I have two nice things to offer you on this Friday morning.

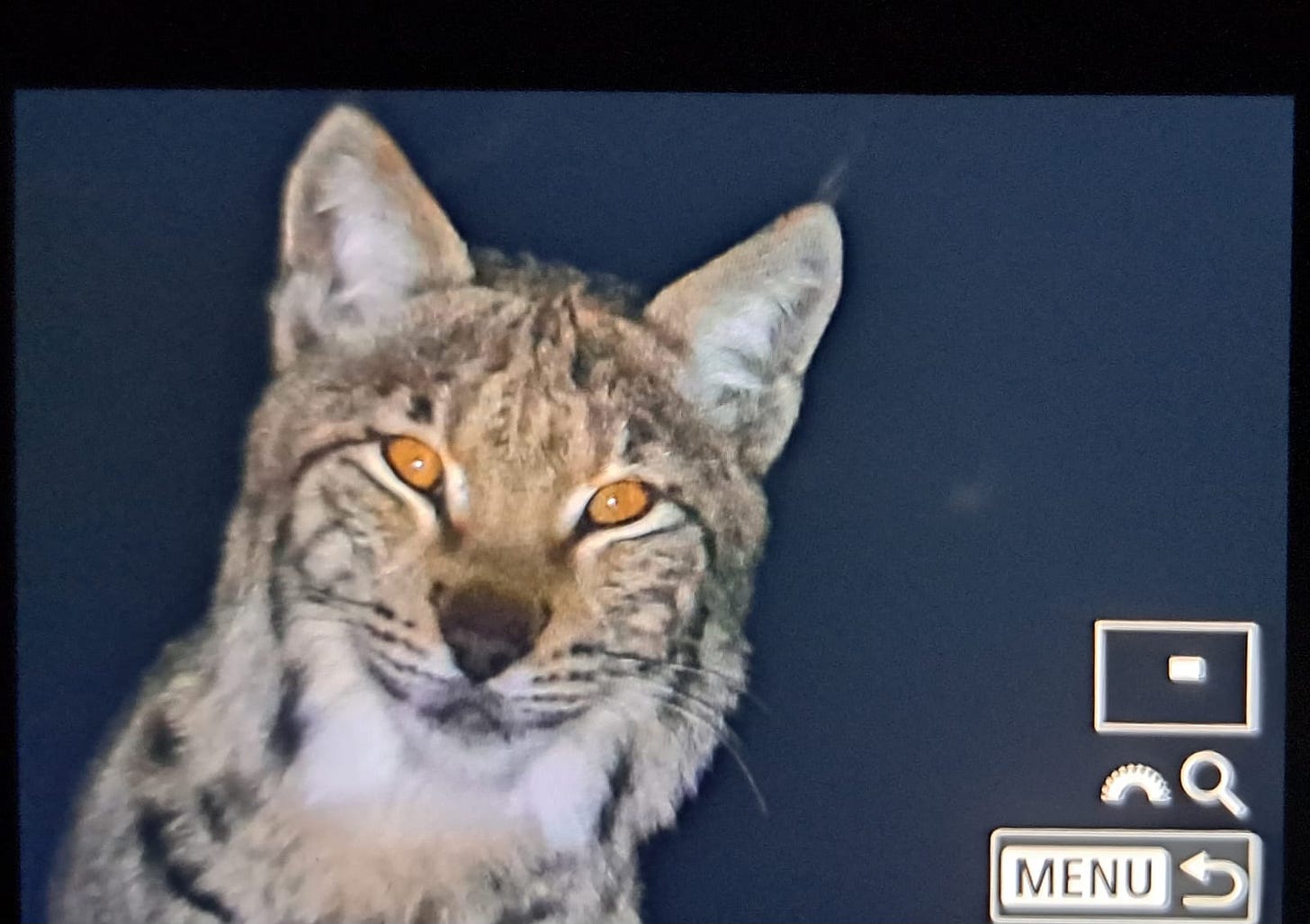

The first is a thank you from Mark Kaptein, our March FUZZ Funds recipient. I sent over your $456 contribution for the month to his anti-poaching unit in South Africa, and he offered in return some really cool photos from his last few guided tours in Poland for the season:

That’s a great mug shot of an Eurasian lynx and a very cool video of two wolves. Poland is a bit of bright spot for wolves within Europe because it granted them legal protection nearly 30 years ago, and large areas of relatively untouched forest habitat have allowed the population to grow. It’s become a source population for wolves to move west into Germany and beyond.

Mark’s headed back to South Africa now and I’ll try to keep in touch to get you some updates on how your FUZZ Funds are getting used. Thanks again so very much to all our paid subscribers and merch supporters who enabled this contribution to his work. Your generosity is appreciated.

And what better time to upgrade and join in for April’s conservation cause?

And for the second positive bit of news: I recently rediscovered a 2020 study that’s too good not to share. It checks all our favorite boxes at FUZZ: it's low-cost, surprisingly effective, easy to implement and improves human-wildlife interactions. And it involves painting faces on cow butts.

Yes, you read that correctly.

The eyes have it: a clever and cheap hack to help reduce the threat to lions

Imagine you're a lion, stalking your prey on Botswana's dusty savanna. You spot a cow, seemingly unaware of your presence. You crouch, ready to pounce... and then you realize the cow appears to be staring right back at you. From its butt.

This isn't a fever dream — it's an innovative conservation solution that's proven remarkably effective. By painting pairs of fake eyes on cattle backsides, researchers discovered an unusual but powerful way to protect livestock from lion attacks.

In Botswana's Okavango Delta region, scientists tested this odd but simple idea across 14 cattle farms experiencing high rates of lion attacks. They divided more than 2,000 cattle into three groups — some got painted eye spots on their rumps, others received simple cross marks (to test whether any obvious marking would work), and the rest were left unmarked as a control group.

The results over four years were striking:

Zero cattle with painted eyes were killed by lions or leopards

Four cross-marked cattle (0.75%) were killed

Fifteen unmarked cattle (1.8%) were killed by these predators

But why do painted eyes work? The research suggests it's not just about having a conspicuous marking - though that helps, as shown by the better survival rate of cross-marked cattle compared to unmarked ones. The significantly higher survival rate of cattle with eye patterns points to something more specific about eyes themselves.

One theory is that the fake eyes trick predators into thinking they've been spotted, removing their crucial element of surprise. Lions and leopards in the study area typically attack from dense vegetation, and all documented predation events occurred within 10 meters of shrubs or woodland. If a lion thinks its cover is blown, it's likely to abandon the hunt.

The solution is remarkably practical. The paint lasts about four weeks before needing reapplication, requires no special equipment beyond basic paint, works with existing farming practices, and costs significantly less than losing cattle.

For farmers operating on slim margins, every cow saved represents significant economic value. But most importantly, when farmers lose fewer cattle to predators, they're less likely to retaliate against lions – as we know from Mark in South Africa, often a major threat to these endangered cats.

The findings aren't just relevant for Botswana. While this was the first test of artificial eyespots against large predators, the principle could work anywhere ambush predators threaten livestock. Sometimes the best solutions to complex conservation challenges are hiding in plain sight – or in this case, painted on a cow's behind.

The study dates back to 2020, and I tried without success to find any follow-up research about whether it’s been adopted more broadly today. If you happen to know, drop a note in the comments — I’d be curious to hear!

No quick links today — we’ll see you on Monday. Have a great weekend!

Thanks for the tip! I think you just bought me some brownie points with IVO!

I’ve heard of talking out of your ass, but this is the I have heard about looking out of your ass.