A 3,000-mile journey to 4 tiny acres

And why your garden (and a commitment to measurement) helped.

By Dan Fletcher

Here is today’s audio edition!

What does conservation success actually look like?

For years, that's been a surprisingly difficult question to answer, especially when it comes to pollinators — the buzzing bees, fluttering butterflies, darting hummingbirds, and countless other creatures whose daily business helps flowering plants reproduce.

Despite the explosion of pollinator gardens across the country—more than a million in the U.S. alone—it's easy to wonder: is any of this actually helping wildlife, or is it just making us feel better? Are these gardens truly effective conservation tools, or merely well-intentioned patches of flowers that let us feel we're doing something while larger habitats disappear?

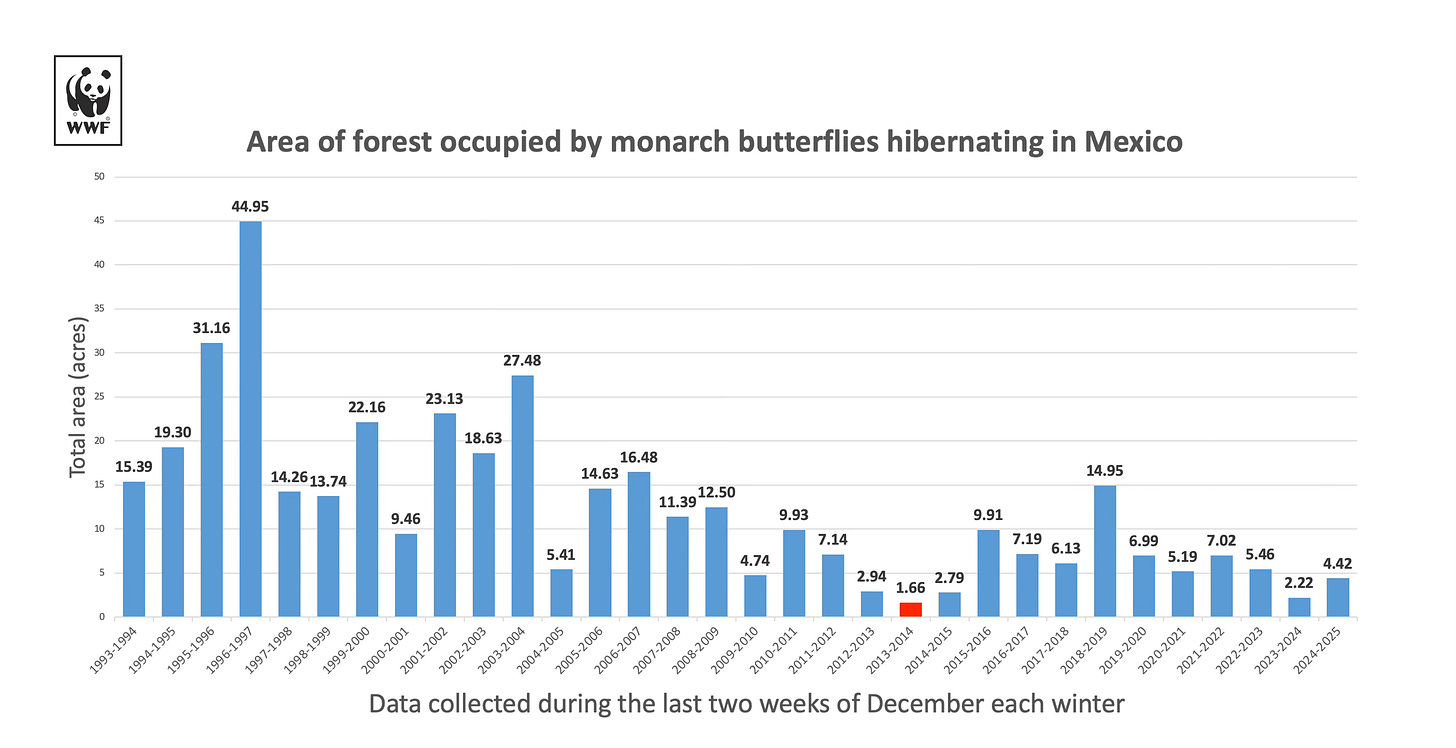

But there’s good news for one of our most beloved pollinators: the eastern monarch butterfly population has nearly doubled over the past year, according to a report just released from Mexico. The butterflies now occupy 4.42 acres of forest during their winter hibernation, up from 2.22 acres last year.

That might sound like a tiny area —and it is— but these few acres represent one of nature's most astonishing concentrations of life. After traveling 50-100 miles per day over a 3,000-mile journey from Canada and the northern United States, millions of monarchs cluster in these small forest patches. The density is mind-boggling: a single tree might host tens of thousands of butterflies. It's a remarkable bottleneck in their life cycle, where the entire eastern population—spread across a continent during summer—converges into a few areas smaller than five football fields.

And this comeback arrives alongside new research highlighting exactly what the monarch success demonstrates: the importance of setting specific, measurable goals in conservation efforts.

A team of ecologists recently published a framework arguing that many pollinator initiatives fall short not because they lack passion, but because they lack clear targets. In their analysis of 43 pollinator initiatives, they found that while 80% had ecological goals, only about 20% set specific, measurable objectives—like increasing the abundance of particular at-risk species. (All the accountants who subscribe to FUZZ are happy right now: if you can't measure it, you can't improve it.)

The monarch program exemplifies this approach perfectly. By measuring forest area occupied during winter hibernation, conservationists have a concrete benchmark to track year-over-year progress. It's not just about "saving monarchs" as a vague aspiration—it's about achieving quantifiable increases in population and habitat.

And while some of this year's population growth can be attributed to better weather conditions along the migration route, it also stems from coordinated conservation efforts across North America. In Mexico, forest degradation in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve decreased by 10%. Meanwhile, in the U.S. and Canada, the widespread planting of milkweed in gardens, parks, and roadsides has created crucial "stepping stones" of habitat for breeding and refueling during migration.

The Million Pollinator Garden Challenge, which encouraged Americans to plant for monarchs specifically, has created thousands of these vital rest stops. Research from Chicago’s Field Museum has shown that even small urban gardens can produce significant numbers of monarch caterpillars when the right plants are present.

The monarch's recovery, while encouraging, remains fragile. The population is still way below historical averages, and threats persist from climate variations, herbicide use, and habitat loss. But having clear metrics allows conservationists to track progress, pivot strategies when needed, and celebrate real victories when they occur.

For all of us planning spring pollinator gardens, the monarch's rebound offers valuable lessons on how to make our efforts count:

Set specific goals for your garden. Rather than just "helping pollinators," decide whether you're specifically supporting monarchs (plant milkweed), targeting native bee populations (include early spring bloomers), or addressing local pollinator decline (ask your regional conservation groups about at-risk species in need of a boost).

Make your goals measurable. Consider simple monitoring like counting monarch caterpillars on your milkweed, photographing pollinators weekly, or participating in community science through programs like Journey North or Monarch Watch, which track migration patterns and breeding success.

Connect your efforts to larger initiatives. Register your garden with national programs, share observations through apps like iNaturalist, or join local pollinator pathways that link individual gardens into meaningful wildlife corridors.

As you plan your garden this season, that little extra thought about what exactly you're trying to achieve—and how you'll know if you've succeeded—could be the difference between a pretty flower bed and a genuinely effective conservation tool.

Quick links!🔗

More proof of just how hard it is to stop animal trafficking — Israeli police have discovered smugglers using heavy-duty drones to fly lion cubs and monkeys across borders from Egypt and Jordan. The investigation—sparked by a viral video showing a monkey chained to a car dashboard and a lion cub in a passenger's lap—has rescued 10 monkeys and four lion cubs so far. Police believe the same criminal networks previously known for smuggling drugs have expanded into exotic wildlife, using industrial drones capable of carrying up to 154 pounds.

Good news for both clean energy advocates and wildlife conservationists — a new study from the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and the University of Cambridge reveals that properly managed solar farms can significantly boost bird diversity. Researchers examining solar installations in East Anglia in southern England found these sites hosted nearly three times as many birds compared to adjacent farmland, with the greatest diversity appearing in solar farms intentionally managed with wildlife in mind. The key seems to be increased habitat variety: solar panel structures provide perching and sheltering spots, while the land between panels can support more diverse plant life, offering seeds and attracting insects that birds feed on.